It’s a question that floats around the internet and summer barbecues alike:

Did Benjamin Franklin invent air conditioning? The idea sounds wild—but it isn’t completely made up.

While Franklin didn’t install central air into colonial homes, he did conduct scientific experiments in the 1700s that helped shape how we understand cooling. His 1758 study with fellow scientist John Hadley proved that evaporation could drastically lower temperatures, even causing objects to freeze in warm air.

Their work didn’t create the air conditioner we know today, but it laid the groundwork for later breakthroughs. So while the keyword “Benjamin Franklin air conditioning” might be a stretch in a literal sense, it’s not wrong to say Franklin helped point us in the right direction—long before the age of thermostats and freon.

And just like so many American inventions that came from practical necessity, Franklin’s ideas were born from asking real-world questions—like how to make life more comfortable during a sweltering Philadelphia summer.

What Did Franklin Do to Stay Cool Without AC?

Back in the 1700s, air conditioning didn’t exist, but that didn’t stop Franklin from thinking about temperature control. He was always looking for ways to solve everyday problems—just like he did with his Franklin stove, which made heating homes more efficient during freezing winters.

As for summer? Franklin’s strategy wasn’t mechanical—it was scientific.

He and Hadley experimented with volatile liquids like alcohol and ether to demonstrate how evaporation could cool down a surface. By blowing air over the liquids as they evaporated from a bulb thermometer, they were able to drop the temperature below freezing—even in a warm room. That discovery was a big deal.

Why? Because it introduced the concept of cooling through evaporation, something that today’s air conditioners, swamp coolers, and even refrigerators rely on.

And Franklin wasn’t the only one making do with the heat. If you visit Lake Ozark Missouri in the 1960s, you’ll see that even generations later, people were still finding ways to beat the summer sun long before central air became standard.

How Did People Stay Cool Without Air Conditioning?

In Benjamin Franklin’s time, cooling down wasn’t about flipping a switch—it was about strategy. People had to work with nature, architecture, and good timing to avoid overheating during sticky East Coast summers.

Here’s how families kept cool in the 1700s:

- Thick stone and brick walls kept the heat out during the day

- Windows were opened strategically to create cross breezes

- Houses were built with large porches and overhangs for shade

- People slept in basements or near cellar doors for cooler nighttime air

- Linen clothing and powdered wigs—yes, even that—helped reflect heat and keep layers light

Franklin, being a man of science and comfort, would’ve used every trick in the book. He reportedly worked and slept with minimal clothing and kept his room well-ventilated.

And no—nobody had ice cubes ready to toss into their lemonade back then. Unless you were wealthy, you weren’t storing ice. It had to be harvested in winter and kept insulated in ice houses, which many early Americans used to preserve food—not cool down themselves.

Want to see how everyday Americans kept surviving brutal summers even centuries later? This look at life in Pursglove, West Virginia in 1938 shows that heat resilience was still a skill long after Franklin’s day.

Did Franklin’s Cooling Experiments Lead to Modern AC?

They didn’t lead directly to the air conditioning units humming in homes today—but Benjamin Franklin’s air conditioning experiments were among the first to explain how cooling really works.

His discovery with John Hadley proved a key scientific principle: evaporation removes heat. This foundational concept is still the basis for:

- Evaporative coolers (swamp coolers)

- Refrigeration systems

- And yes—modern AC units

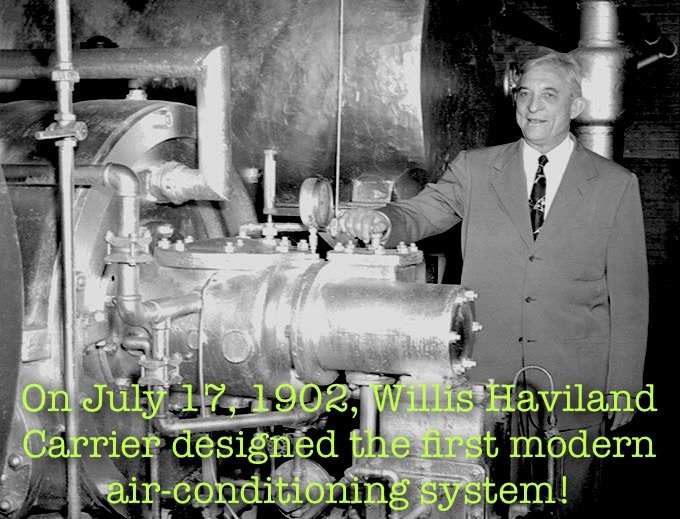

Franklin never set out to create a climate control device, but he was laying bricks on the path. Without that scientific breakthrough, Willis Carrier’s 1902 invention of mechanical air conditioning might’ve come later—or not at all.

It’s the same story told over and over again in American history—inventions that changed the world started with someone curious enough to experiment. You can see this mindset again in the early innovation behind the Stockholm Telephone Tower, where imagination and practicality collided long before modern tech was possible.

How Did People Sleep at Night Without Air Conditioning?

If you’ve ever tossed and turned in a hot house with a broken AC, you’ve had a small taste of what summer nights were like in the 1700s. But for folks like Benjamin Franklin, this was life every night of the season.

So what did they do?

- Sleep in shifts: People sometimes napped in the coolest hours (early morning or late evening)

- Damp sheets: Some soaked bed linens in water and let the breeze cool them

- Stone or marble surfaces: If you were wealthy, you might have a stone floor to lie on for relief

- Basement bedrooms: The ground level offered a break from the upper-floor heat trap

- Nightclothes made from breathable linen: Franklin was known for keeping things minimal—literally

The focus was always on airflow, timing, and natural materials. Homes were often designed with sleeping porches or shuttered windows positioned to pull in night air and push out the trapped heat of the day.

You can feel the evolution of those survival habits in later decades too. For example, check out Frozen in Time: The Woman on the Mississippi River in 1905—a moment frozen in literal cold, showing how extreme weather shaped everything from sleep to survival, depending on the season.

When Was Air Conditioning Actually Invented?

Despite Franklin’s early breakthroughs, the first true air conditioning system wouldn’t arrive until more than a century later.

Here’s a quick timeline:

- 1758: Franklin and Hadley prove that evaporation can lower temperature

- 1830s–50s: Ice delivery becomes big business for wealthy homes and cities

- 1902: Willis Carrier invents the first mechanical AC system for a printing plant

- 1931: The first window air conditioner is created

- 1950s: Home AC becomes more common in suburban American households

So while Benjamin Franklin air conditioning wasn’t a real invention, his scientific work absolutely paved the way. He asked the questions. Carrier answered them—with compressors and coils.

And during that long gap between Franklin and Carrier? People did what they had to do. Stories like How People Kept Food Cold Before Refrigerators show just how inventive and persistent early Americans had to be when facing daily discomforts—with zero gadgets to help.

Franklin’s generation didn’t have AC, but they had grit, science, and enough creativity to keep pushing forward until someone made it happen.

Was Franklin Trying to Solve the Heat Problem?

Not directly—but that’s what makes him so fascinating.

Benjamin Franklin wasn’t trying to invent air conditioning, but he was obsessed with comfort, science, and how to make life more livable. Whether it was his Franklin stove warming homes in winter or his lightning rod protecting them from fire, his work always blended curiosity with practicality.

His cooling experiments weren’t about luxury—they were about understanding. He wanted to know how temperature worked, why evaporation cooled, and what that meant for everyday life. That mindset—questioning, testing, improving—is exactly what made Franklin’s contributions so far-reaching.

That same attitude can be seen in other American inventors and tinkerers. For example, The 1944 Brogan Doodlebugwas another piece of creative engineering built by someone trying to solve a common problem: transportation on a budget.

Franklin simply aimed his intellect at everything, including the weather.

What Can We Learn From Franklin’s Approach to Comfort?

The takeaway here isn’t just about Benjamin Franklin air conditioning—it’s about how early Americans tackled discomfort without modern machines.

Franklin reminds us that invention starts with observation. He didn’t need a factory or a team of engineers. Just a thermometer, a few chemicals, and a curious mind. And from that came one of the earliest documented experiments in air cooling.

We can still learn from that mindset today—especially as we face modern energy concerns, climate extremes, and the desire to live more sustainably. In a world that leans heavily on machines, Franklin’s curiosity-driven approach feels surprisingly fresh.

And it’s not just about AC. This idea of practical invention and day-to-day survival stretches across time. Look at how families got by in Pocahontas County, West Virginia in 1921—or how people managed heat, cold, food, and illness long before electricity was common.

Franklin didn’t invent the air conditioner. But without his early cooling experiments, we might not be chilling in climate-controlled rooms today.

And honestly? That’s pretty cool.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases through some links in our articles.